It was a clear sunny morning. The sunbeam was falling across the main hall of the gallery while a young man was leaning against the white wall. He turned aside to the window, which someone had left ajar, and lit a cigarette. One could easily spot the reflection of Yuanfang’s self-portrait in the window glass. Framed within a camera lens, juxtaposed by a female figure in swimsuit facing the vast azure ocean, this sight seemed serene yet agitating. The sexual tension was striking: the outfit, the bareness of the skin and the posture. Nevertheless, everything was morphed into a sense of peacefulness through the blazing stillness of the colour of the ocean.

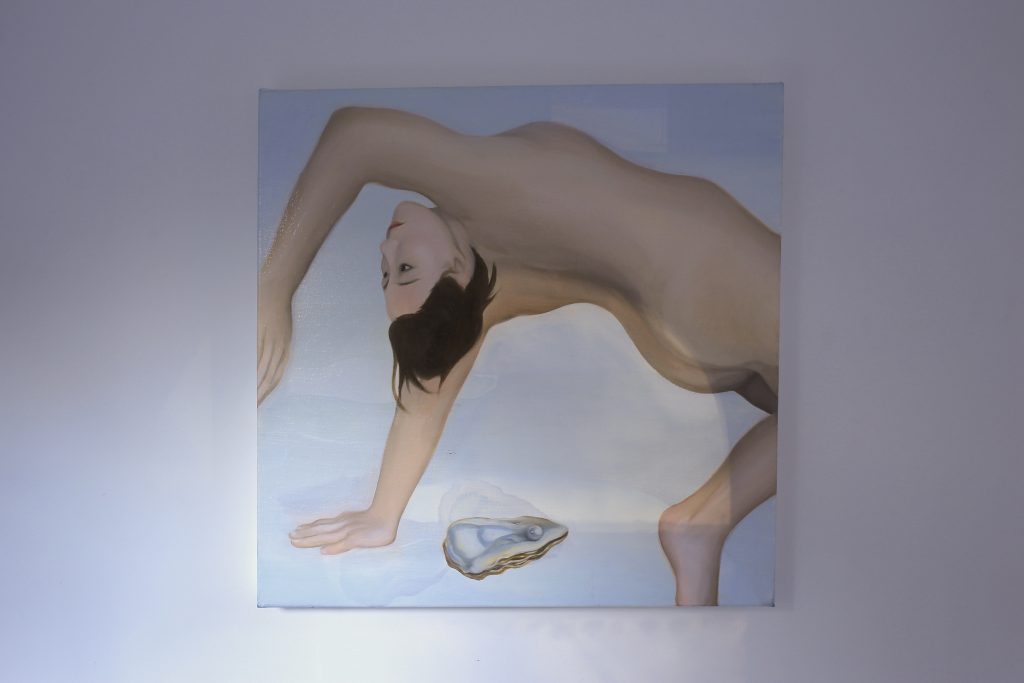

The exhibition was titled Un Bout De Moi, which literally translated into A Piece Of Me. The Chinese title, however, played with an English phonetic mix-up, is 一小块儿肉 (a piece of meat), which might seem absurd to some, is a de-facto reference to the subject of anything sexual. The idea that the Chinese culture would use meat, or a euphemism for flesh or anything that remotely relates to sexual desires, is not the least surprising. The connotation of the exhibition title, however, is intriguing. Living in the era of #MeToo or thereafter, one cannot be more careful with the implications and materialisations of women’s body, especially faced with severe consequences of an ascending cancel culture. Yet the artist herself did not seem to care for such suggestion: the idea that a part of herself – be it her flesh, her emotion, or her artistic expression – is for no one to exploit. In other words, no one is to deny her the emblem that she chose for her own body. Therefore, one cannot help but noticing the contradicting contrast within each single piece of work shown: a daring nude of the artist herself, bending backwards, shielding a pearl oyster, full of sexual tension yet delicately peaceful with the intended posture, set in a purposely mixed greyish blue; the self-portrait that looks into nothingness or somethingness; a lying-down torso of a female in a greyish blue loose gown. This colour was of often use in Yuanfang’s works, like the repetition of squares in Mondrian’s colour blocking or Andy Warhol’s silver print of Monroe, benign to the audience, yet of great impact to the makers themselves.

It is often in these tiny details that some audience would comment: my child could have made this within an hour. Not unheard of, but the definition of child prodigy in art is not as simple as the capability to complete a painting of certain colour mix within one earth hour. But one can always dream and that is all that matters when it comes to art after all.

To be an artist, of whatever sort, more than technique is required. To think of Yuanfang’s works being pieces of her, literally or metaphorically, is a path to understand an artist, a female, a person, and to comprehend her emotions, desires and the complexities of her bare existence. Unlike asking for the price of a cut of fillet mignon, it takes more than just the blood and flesh to pierce through the canvas and the paint, for minutes, hours and sometimes ages. So there she was, lying on the floor, in a baggy turquoise dress, and the oblivion.

Leave a Reply